I haven’t been posting much lately as I’ve been busy with other things. I have, however, recently come across this article about the work of Stephan Lewandowsky. He is a cognitive scientist in the School of Experimental Psychology at the University of Bristol. He has published a couple of papers about why some people seem to reject (deny?) many of the findings of climate science. The post that I’m reblogging is reporting on a couple of his papers and suggesting that there is a link between having a libertarian (free-market) ideology and rejecting climate science. If you’ve read any of my other posts, you’ll know I have real issues with the basic tenets of free-market thinking and with those who reject climate science, so this post certainly gels with my thinking and it is interesting that it is based on published work in cognitive science. Doesn’t make it right, I guess, but I would recommend giving it a read.

Category Archives: Climate change

The integrity of universities

There’s a very interesting (in my opinion) article by George Monbiot in the Guardian today. The article is called Oxford University won’t take funding from tobacco companies, but Shell’s OK. The basic premise is that universities should be acting for the common good, or as George Monbiot puts it

the need for a disinterested class of intellectuals which acts as a counterweight to prevailing mores.

I have to say that I agree completely with this. It has always surprised me how disinterested UK academics can be. I had always assumed that university academics had a role to play in defining what is acceptable in our societies. They are meant to be the intellectual members of our society; the people who think. If academics are reluctant to be involved in this, then who else is going to do it? This isn’t to say that everyone should bow to the views of academics, simply that academics should feel free to question what is accepted in our societies.

There are probably many reasons why UK academics are reluctant to engage in discussions about our society. One may simply be that academics have become very focused. They see themselves as experts in quite specific areas and so don’t see it as appropriate to engage in areas outside their expertise. There is some merit to this, but it is a bit disappointing – in my opinion. Another may be that there is now quite a lot of pressure on academics. Universities have become very bureaucratic and there is quite a strong publish-or-perish attitude. Academics don’t have much spare time to contemplate the merits – or lack thereof – of our societal mores. Universities have also become much more like businesses. The goal is to maximise teaching and research income and, hence, academics are discouraged from doing anything that doesn’t enhance a university’s ability to generate income.

Personally, I think the latter is the main reason why universities (in the UK) are no longer hotbeds of dissent. We are publicly funded and hence need to do what is expected of us. I’m often very critical, for example, of the Research Excellence Framework (REF2014) and even though most seem to agree, the typical response is “we just have to do this”. Well, yes, but do we have to do it happily. If we think it is damaging what we regard as strengths of the UK Higher Education system, shouldn’t we be making it clear that we’re doing it under duress. There’s also this view that we have to do what is best for UK PLC (i.e., what will best help economic growth in the UK). In a sense, I agree with this. What I disagree with is how we’re influenced to do this. University research has, for many decades, had a very positive impact on economic growth. However, this didn’t happen because politicians told universities to do this. It’s because people recognised the significance of some piece of research and used it to develop something that had economic value. It’s also largely unpredictable. It’s certainly my view that telling us to start predicting the economic benefit of our research will do more harm than good.

The final thing I was going to say regards the main thrust of George Monbiot’s article. If there is increasing evidence that global warming is happening (as there is) and if there is evidence that such warming could lead to life-threatening climate change, shouldn’t the universities where this research is taking place act as though it’s important. Maybe universities shouldn’t be accepting funding from oil companies, if their own research indicates that we should significantly reduce our use of fossil fuels. I have heard some argue that we shouldn’t worry about the provenance of our funding as we’ll typically do good things with whatever money we can get. I think this is naive. The idea that one can take funding from oil companies without being influenced by the source of this funding seems highly unlikely.

Addicted to Watt!

Despite my rather unpleasant encounter with another commentator on the Watts Up With That site, I find myself slightly addicted to going back and checking for new posts and comments. It’s not because I enjoy it. I think it’s because I’m still slightly shocked about the encounter I had a few days ago and just wanted to see if such encounters are common or not. I didn’t search very hard, but I did find a number of fairly aggressive exchanges between some commentators.

What I found most “interesting” is the style of the rhetoric. Quite a few posts were extremely condescending and regularly seem to contain things like “couldn’t stop myself from smiling/laughing/grinning at how silly” some climate scientist had been. On almost every single post, the first set of comments would invariably be short, snappy, snarky, sarcastic remarks about how idiotic or stupid a particular study had been. It seems like an online version of mob rule. A classic example of confirmation bias. Noone who was critical of a some piece of climate science ever seemed to say “… but this aspect of the work looks interesting.” It was almost always complete dismissal. If this really is a group of people who claim to be interested in engaging in scientific discussions to better understand the science of climate change, they’re certainly going about it in a way that I don’t think any scientist I know would recognise as suitable.

There also seem to be some commentators who dominate the discussions. The one I encountered (richardscourtney) seems to be held in quite high regard. The impression I have is that he sees himself as some grand figure who is there to clarify things for those who are uncertain about something, and to challenge those – in the interests of science – who make statements with which he disagrees. His style of rhetoric is regularly aggressive but also extremely sarcastic. Thanking people for responding to something and then launching into some attack on what’s been said. What’s ironic, is that he often claims to be challenging unsubstantiated statements by making mostly unsubstantiated statements of his own. It’s as if by saying something forcefully and definitely it makes his statement true, while another person’s statements are somehow anti-scientific nonsense. His comments also have lots of “NO!” and boldface words to, I assume, make his statements more authoritative.

One of the common themes on the Watts Up With That site is that there is something fundamentally wrong with climate scientists. They’re either lying, or incredibly stupid, or naive, or subconsciously influenced by some inherent bias in the climate science community. They simply can’t be trusted and need to be constantly mocked or verbally abused! I was interested to see a post claiming that Weather – not climate – caused the brief surface melt in Greenland last summer. This paper was quite well received. The lead author on the paper was Ralf Bennartz, a Professor at the University of Wisconsin. I then discovered another post called Old models do a bad jobs so a new models says “warming must be worse”. This was about a paper describing attempts to include – more realistically – the influence of clouds in climate models. This post seemed to have the normal level of mockery, and the comments seemed to be particularly dismissive of this work. But hold on a minute, one of the authors seems to be the same Ralf Bennartz who was lead author on what was an acceptable paper suggesting that weather, not climate, influenced ice cover in Greenland last year. I’m not suggesting that you’re not allowed to criticise one paper by a particular person while regarding a different of their papers as being quite good. What I do think, however, is that you can’t accuse climate scientists of being inherently dishonest and then regard positively a paper by a climate scientist if it happens to say something that suits your ideology.

Now, I imagine that if any credible scientists were actually to read this post, they would probably think – “did you expect it to be different?”. Well, I’ve read enough about climate change to have been aware that this was a distinct possibility. I think I had hoped that maybe it would be possible to engage with climate skeptics in a manner that was at least consistent with decent scientific discourse. I don’t think you need to change someone’s mind in order to make such an exchange worthwhile. It does seem, according to my experience at least, that this is virtually impossible on the Watts Up With That site. I should acknowledge that there may well be other sites that support the results of climate science on which it would also be difficult. That, however, doesn’t excuse the behaviour of those on the Watts Up With That site. The other thing I would say is that I don’t like the idea of being criticial of something without at least having some personal experience that justifies such a criticism. Having both read a number of posts and a large number of comments on the Watts Up With That site, and after a rather unpleasant exchange with one of their regular commentators, I certainly feel justified in being highly critical of the manner in which the site both presents and discusses climate science. It’s quite amazing that it seems to have won a “Best Science Blog” 3 times. Just as many scientists would be happy to acknowledge that the paper with the most citations isn’t necessarily the best paper, I suspect that many would also agree that winning a “Best Science Blog” award doesn’t guarantee that you’re actually the best science blog. I certainly hope that’s the case because heaven helps us if this is indeed the best science blog.

The Economics of Climate Change

I came across an article by Ross McKitrick in the Financial Post called We’re not screwed. It is essentially a response to the media coverage of the Marcott et al. (2013) paper in Science that I wrote about in an earlier post.

What I found a little surprising is that Ross McKitrick is a Professor of Economics at the University of Guelph. It’s not that I think that economists shouldn’t discuss climate change but – in the article he wrote for the Financial Post – he was being quite specific with his criticisms of the methods used by Marcott et al. (2013). I’m sure he’s a bright person, but climate science is difficult and it seems quite presumptuous that a Professor of Economics somehow thinks that they know better than professional climate scientists (I could be snide and suggest that if economists were unable to predict a global economic catastrophe they should be slightly careful about assuming that they can make predictions about global warming, but that wouldn’t really be fair).

One of Ross McKitrick’s colleagues (in the sense that they’re written articles together) is Stephen McIntyre who has a BSc in Mathematics and an MA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics. It’s starting to seem to me that a number of those who are skeptical of the claims of climate science have backgrounds in economics. I looked at the website of the Global Warming Policy Foundation one of who’s founders is Lord Lawson, an ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer. About 8 of their academic advisors have some background in economics. It appears – to me at least – that economics is more highly represented than any other single discipline.

I haven’t done a proper study to see if there really are more economists who are climate skeptics than any other discipline, but it does seem that way. One of the claims that climate skeptics make is that climate scientists are biased and benefit from suggesting than anthropogenic global warming is real. I find it surprising that noone has really tried to make the counterclaim that it is odd that so many climate skeptics happen to have a background in economics. One reason may simply be that scientists don’t typically want to spend their time debating educated lay-people who think they know better. Normally you can ignore such people and they simply go away. When they have influence and can get their views presented in somewhat reputable media outlets, it’s not that simple. I don’t really think that climate scientists should engage in a battle with those who are skeptical. It’s not really their role and the science will eventually be settled. It’s just a little disappointing that those who have little explicit experience with climate science (or with science at all) somehow seem to have credibility with certain sectors of society. Maybe it’s because they’re saying what that sector wants to hear?

The Green Agenda

There seems to be quite a lot of rhetoric about the cost of climate policies with many essentially suggesting that it will cost a lot of money and that it is some kind of government conspiracy. There is even a Fox Business News report titled The Green Tyranny which seems to be suggesting that government regulations have gone too far.

Something that has always confused me about this is that providing energy is always going to cost money. Extracting fossil fuels is not free and so that it will cost money to provide alternative energy sources is obvious. The real questions should be is it more expensive than using fossil fuels, what is the long-term cost compared to fossil fuels, and how does it compare – environmentally – to fossil fuels (or, what are the additional costs). Of course, I think that increasing CO2 levels in our atmosphere is leading to climate change and that we should be acting to mitigate this as soon as possible. However, even if you disagree, fossil fuels will eventually run out or become extremely expensive to extract, and so developing alternative technologies seems to make sense. The question is, should we start now, or can we wait. I think we should be starting now, but I’d be happy to hear arguments as to why we should be waiting.

There is another factor though – in my view at least – and that is whether or not you need to import oil and gas in order to provide your energy needs. I found the two figures below on the Energy Administration Information website. The top shows the UK’s natural gas production and consumption from 2000 to 2011 and the bottom shows the same for oil. What is clear is that until about 2004, the UK was producing more natural gas and oil than it was consuming. Today we only produce about 60 – 70 % of what we use and the fraction appears to be dropping quite dramatically.

This clearly means that we must be importing a significant fraction of the natural gas and oil that we use. What does this cost? I found the figure below on a website called The Oil Drum. It shows the UK’s trade balance in energy products and shows that until 2004, there was an oil and gas trade surplus. Today there is a deficit. We’re spending about £5 billion per year to import oil and gas. What’s more, in 2000 there was a trade surplus in energy products. Today it makes up 15 – 20% of the total trade deficit and – as far as I can tell – will continue to increase as we import more and more of our oil and gas.

What I’m suggesting is that even if you don’t feel that we should be worried about climate change, surely you should be concerned about the UK’s increasing need to import oil and gas. We’re currently spending about £5 billion a year importing oil and gas and it seems (given that the fraction we can produce is decreasing quickly) that this is likely to increase. Wouldn’t it be better if we could spend this money paying people in the UK to develop and maintain alternative energy sources? I think it would, but feel free to let me know if you disagree.

Second fastest annual rise in carbon dioxide

A recent article in the Guardian reported that 2012 saw the second highest annual rise in CO2. This was 2.67 parts per million (ppm) measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory on Hawaii. The article also included a link to a paper published in Science that presented reconstructions of regional and global temperature for the past 11,300 Years (Marcott et al., 2013, Science, 339, 1198-1201).

It seems as though many who are skeptical (deny) man-made climate change often say things like “where is the paper that says ….”, so I thought I would highlight some of the results presented in this paper. Below I reproduce the abstract. Quite a balanced abstract containing a summary of the results and a conclusion, at the end, that suggests that by 2100 the global surface temperatures will be higher than at any time in the past 11,300 years.

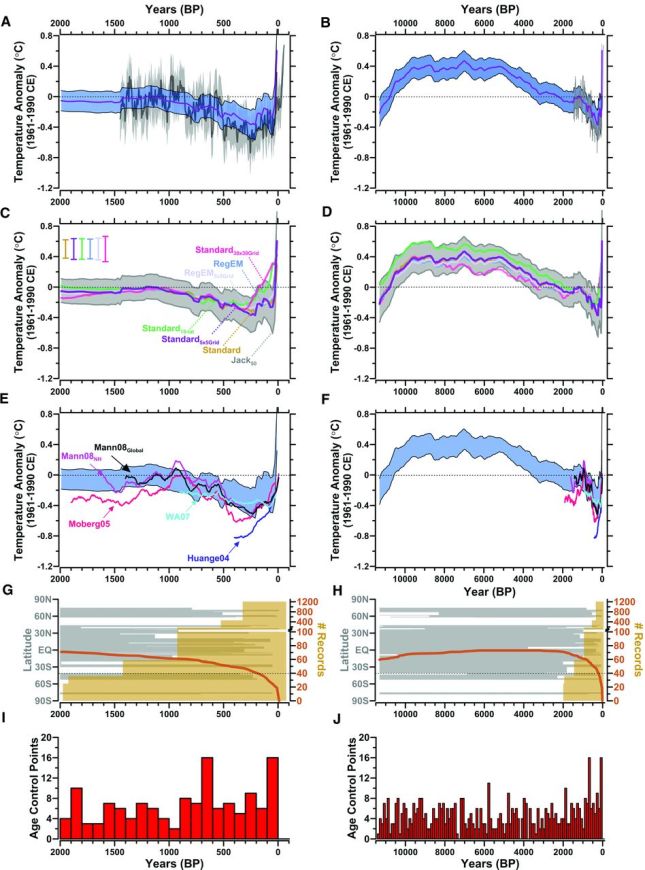

Surface temperature reconstructions of the past 1500 years suggest that recent warming is unprecedented in that time. Here we provide a broader perspective by reconstructing regional and global temperature anomalies for the past 11,300 years from 73 globally distributed records. Early Holocene (10,000 to 5000 years ago) warmth is followed by ~0.7°C cooling through the middle to late Holocene (<5000 years ago), culminating in the coolest temperatures of the Holocene during the Little Ice Age, about 200 years ago. This cooling is largely associated with ~2°C change in the North Atlantic. Current global temperatures of the past decade have not yet exceeded peak interglacial values but are warmer than during ~75% of the Holocene temperature history. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change model projections for 2100 exceed the full distribution of Holocene temperature under all plausible greenhouse gas emission scenarios.

Below is one of the main figures from the paper. It shows the temperature anomaly and compares various different methods. The left-hand panel goes back 2000 years, while the right-hand panel goes back 11,300 years. There is good agreement between the different methods and it seems clear that the temperature anomaly today is higher than it has been for the past 2000 years.

Comparison of various methods for determining the temperature anomaly for the past 2000 years (left-hand panel) and for the last 11,300 years (right-hand panel). Figure from Marcott et al. (2013).

It, however, appears (from the righ-hand panel in the above figure) that there may have been periods during the Holocene when the temperature may have been higher than it is today. However, I include – below – some of the concluding text from the paper.

Our results indicate that global mean temperature for the decade 2000–2009 (34) has not yet exceeded the warmest temperatures of the early Holocene (5000 to 10,000 yr B.P.). These temperatures are, however, warmer than 82% of the Holocene distribution as represented by the Standard5×5 stack, or 72% after making plausible corrections for inherent smoothing of the high frequencies in the stack (6) (Fig. 3). In contrast, the decadal mean global temperature of the early 20th century (1900–1909) was cooler than >95% of the Holocene distribution under both the Standard5×5 and high-frequency corrected scenarios. Global temperature, therefore, has risen from near the coldest to the warmest levels of the Holocene within the past century, reversing the long-term cooling trend that began ~5000 yr B.P. Climate models project that temperatures are likely to exceed the full distribution of Holocene warmth by 2100 for all versions of the temperature stack (35) (Fig. 3), regardless of the greenhouse gas emission scenario considered (excluding the year 2000 constant composition scenario, which has already been exceeded). By 2100, global average temperatures will probably be 5 to 12 standard deviations above the Holocene temperature mean for the A1B scenario (35) based on our Standard5×5 plus high-frequency addition stack (Fig. 3).

Probably the strongest statement is that within the past century global average temperatures have gone from some of the coolest of the last 11,300 years to some of the warmest. If this continues, as is expected, by 2100 global average temperatures will be significantly higher than the mean of the Holocene. Here we have a very recent peer-reviewed paper in a major scientific journal saying that within the next 100 years, average global temperatures will be higher than they’ve been for the last 11,300 years. The paper doesn’t actually say that such high temperatures could have a catastrophic effect on man, but I think we can probably conclude that it won’t be ideal.

Global warming – the basics

I’ve been getting into various online debates with climate skeptics. It typically doesn’t turn out well and eventually I just give up. It very rarely remains a discussion about the science. It often becomes pedantic or starts to become a discussion about how can we trust climate scientists given that they apparently somehow benefit from pushing a climate change agenda. I always find this an extremely odd argument given that the amount of money going into climate science is miniscule compared to the amount of money involved in the fossil fuel industry. The incentive for the fossil fuel industry to undermine arguments in favour of developing alternative energy seems much greater than the incentive for climate scientists to push some kind of agenda that isn’t supported by the scientific evidence.

Something that is regularly said is that there has been a pause in global warming since 1997. This is based on analysis of temperature anomaly data which results in a trend (since 1997) that is smaller than the 2σ errors and hence suggests that we cannot claim that there has been warming since 1997. I’ve addressed this in a number of places, but essentially this is not that surprising and there are many instances in the last 30 years where 15 years or more were needed to determine a statistically significant warming trend. Below, I’ve included a figure showing the monthly temperature anomaly data since 1880. The possible flattening in the running average (thick solid line) in the last bit of the very noisy data is what some are using to claim that there has been a pause in global warming.

Okay, so let’s imagine that the temperature anomaly data has indeed been flat since 1997. I’m not claiming that it has, but let’s imagine that it has. Basing whether or not global warming is happening on temperature anomaly data alone is simplistic and illustrates a lack of understanding of what global warming is at a more fundamental level. Global warming is fundamentally an energy imbalance in which we receive more energy from the Sun than we radiate back into space. In an earlier post I included a couple of figures showing that there has been a measured energy excess for 30 years or more. This tells us that global warming is happening, irrespective of what the temperature anomaly is doing. The basic point is that this excess energy doesn’t only increase surface temperatures, it also melts ice and increases the heat content of the oceans.

So, can we see evidence of excess energy going into melting the ice at the poles or into heating the oceans. Indeed we can. The figure below (taken from Stroeve et al, GRL, 39, L16502, 2012) shows September sea ice extent in the Arctic. The x-axis goes from 1900 to 2100 and the red and blue lines are from models. The black line is the observed sea ice extent and extends from 1950 to 2011. What seems clear is that the Arctic sea ice extent in September has dropped faster than even the models predicted.

What about the heating of the oceans? Well, the figure below shows the heat content of the oceans in Joules. It’s clear that it has been increasing pretty steadily since sometime in the 1960s. It’s also quite an impressive amount of energy. It’s increased by more than 1023 Joules since the 1960s and this is only down to a depth of 700m.

The last figure I wanted to show was one showing the heat content of the oceans and of the land and atmosphere, from 1950 to the mid 2000s. Again, they’ve both been increasing steadily since the 1960s, but the amount of energy going into the oceans dwarfs that going into the land and atmosphere.

So, what’s the point of this post? Well, it was simply to illustrate that global warming isn’t simply about increased global surface temperatures. Increases in the global surface temperature is what we are worried about, but global warming is a continual increase in the amount of energy being absorbed by the whole system. This includes heating the oceans and melting polar ice. The data seems to clearly indicate that the amount of polar ice is decreasing and the amount of energy going into the oceans is also increasing. This is global warming. Ignoring the oceans and the polar regions and focusing only on global surface temperatures is simplistic and shows a significant lack of understanding of what global warming is. Being skeptical of science is good. Basing skepticism on a subset of the data that doesn’t represent the whole picture is not good and if people are going to be skeptical of climate science, they should at least attempt to understand the science at some basic level.

Climate change – statistical significance

I’ve written before about the claim that there has been no warming for the last 16 years. This is often made by those who are skeptical – or deny – the role of man in climate change. As I mentioned in my earlier post, this is actually because the natural scatter in the temperature anomaly data is such that it is not possible to make a statistically significant statement about the warming trend if one considers too short a time interval.

The data that is normally used for this is the temperature anomaly. The temperature anomaly is the difference between the global surface temperature and some long-term average (typically the average from 1950-1980). This data is typically analysed using Linear Regression. This involves choosing a time interval and then fitting a straight line to the data. The gradient of this line gives the trend (normally in oC per decade) and this analysis also determines the error using the scatter in the anomaly data. What is normally quoted is the 2σ error. The 2σ error tells us that the data suggests that there is a 95% chance that the actual trend lies between (trend + error) and (trend – error). The natural scatter in the temperature anomaly data means that if the time interval considered is too short, the 2σ error can be larger than the gradient of the best fit straight line. This means that we cannot rule out (at a 95% level) that surface temperatures could have decreased in this time interval.

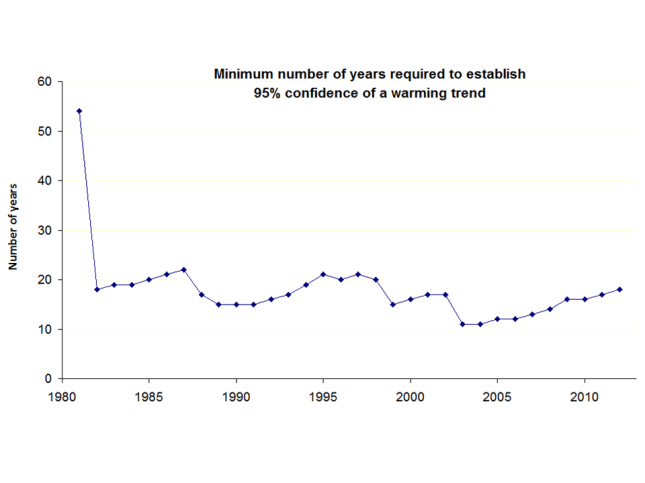

We are interested in knowing if the surface temperatures are rising at a rate of between 0.1 and 0.2 oC per decade. Typically we therefore need to consider time intervals of about 20 years or more if we wish to get a statistically significant result. The actual time interval required does vary with time and the figure below shows, for the last 30 years, the amount of time required for a statistically significant result. This was linked to from a comment on a Guardian article so I don’t know who to credit. Happy to give credit if someone can point put who deserves it. The figure shows that, in 1995, the previous 20 years were needed if a statistically significant result was to be obtained. In 2003, however, just over 10 years was required. Today, we need about 20 years to get a statistically significant result. The point is that at almost any time in the past 30 years, at least 10 years of data – often more – was needed to determine a statistically significant warming trend and yet noone would suggest that there has been no warming since 1980. That there has been no statistically significant warming since 1997 is therefore not really important. It’s perfectly normal and there are plenty of other periods in the last 30 years were 20 years of data was needed before a statistically significant signal was recovered. It just means we need more data. It doesn’t mean that there’s been no warming.

Pressure on Venus

I’ve written before about the Runaway greenhouse process on Venus. In the case of Venus, this was an entirely natural process and such a process is unlikely to take place on Earth as we have locked much of our CO2 into carbonate rocks. It is, however, illustrative of how the greenhouse effect can significantly influence the climate on a terrestrial planet.

I recently became aware of a post on the Watts up with that website claiming that the reason Venus has such a high surface temperature is because of the extremely high pressure. There are lots of equations and graphs and quite a convincing argument, but it is simply wrong. The reason I thought I would write about this is that when I saw that post I remembered a senior Professor in an Earth Science department at a US university telling me the same thing a few years ago. At the time I thought, “that’s interesting”, but didn’t think any more of it. If a professor of Earth science can get it wrong, no wonder it’s easy enough to make it seem as though the argument makes sense.

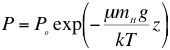

So why is it wrong. Basic atmospheric modelling is not all that difficult. To model an atmosphere you need an equation of state relating pressure, density and temperature. Typically you would use something like

where P is the pressure, ρ is the density, T is the temperature, mH is the mass of a hydrogen atom, and μ is the mean molecular weight. On Earth, the most common molecule in the atmosphere is N2 so μ ~ 28, while on Venus it is CO2 so μ ~ 44.

Atmospheres will settle into a state of hydrostatic equilibrium. This means that the downward force of gravity will be balanced by an upward pressure force. This allows us to write

where g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m s-2 on Earth and 8.9 m s-2 on Venus) and z is the height in the atmosphere. We can solve the above equation to write

where Po is the pressure at the base of the atmosphere. The term kT/μmHg is known as the scaleheight and tells you the vertical distance over which the pressure drops by a factor of 1/e (1/2.72). It increases with temperature and so the hotter the atmosphere, the slower the pressure drops with height.

Now we have a set of equations that essentially allow us to solve a basic atmospheric structure problem. However, there are two things we don’t know. What is T and what is Po? Where does the temperature come from? Well it comes from the balance between the amount of energy that the planet receives from the Sun and the amount it re-radiates into space. The temperature of the planet must be such that it re-radiates as much energy back into space as it receives. The pressure at the base of the atmosphere is related to the atmospheric density through the equation of state. The atmospheric density depends on how much atmospheric material there is in the atmosphere. I’ve kind of implied that it is simple, but in truth it is not that simple. The planet’s temperature depends on the composition of the atmosphere. To solve the problem properly, you need to include the influence of the atmosphere on the incoming and outgoing radiation. This will determine the equilibrium planetary temperature and the variation of temperature with height. You also need to iterate until the density structure gives the correct total mass. However, what determines the pressure profile in the atmosphere is the temperature of the atmosphere and the amount of material in the atmosphere (i.e., the density). The pressure does not determine the temperature. If there was no incoming energy, the atmosphere would lose energy, the temperature would drop, the scale height would decrease and the atmosphere would collapse onto the surface of the planet. When it was cold enough, the molecules would become liquids or solids and the atmosphere would disappear. In other words to have a steady atmospheric pressure, you need incoming energy from the Sun. To re-iterate, the temperature determines the pressure, the pressure does not determine the temperature.

So the reason Venus has a high surface temperature is not because of the high pressure. The reason it has a high pressure is because of the high temperature and density. We can illustrate this by considering the Earth. Atmospheric pressure at sea level is 105 Pa. Atmospheric density at sea level is about 1.2 kg m-3. The atmosphere is primarily nitrogen so μ = 28, mH = 1.67 x 10-27 kg, and k = 1.38 x 10-23 m2 kg s-2. If I plug these numbers into the equation of state shown at the beginning of the post I get T = 338 K. So, the Earth’s temperature is because of our atmospheric pressure, not because of the energy we receive from the Sun! No, clearly this is wrong. If the temperature and density determine the pressure, I can then use the density and pressure to calculate the temperature. It doesn’t mean that the pressure determines the temperature, it just means there’s a relationship between pressure, density and temperature.

Given that I’ve linked to the post on the Watts up with that website, this would normally appear as a comment. I’ll be interested to see if it does indeed appear as such. It’s clear that claiming that the high surface temperature on Venus is due to its high pressure is wrong. Anyone who understands physics would accept this and the author of the post claiming this should recognise this and be willing to acknowledge their mistake. I would have much more time for those who are skeptical of man-made climate change if they were willing to accept when they are wrong. That is essentially the scientific process. Mis-using a set of equations to make a spurious claim is not.

Obama on climate change

In his inauguration speech Barack Obama has unequivocally stated that the US should act to combat climate change; that failing to do so would be a betrayal of future generations. It’s a great speech and what he says (in my view at least) makes perfect sense. Acting to reduce man’s influence on the climate is both necessary, if we want to avoid catastrophe, and also makes economic sense. I just hope he sticks to this pledge. It will be difficult given the political climate in the US, but it could leave an amazing legacy if he is succeeds.